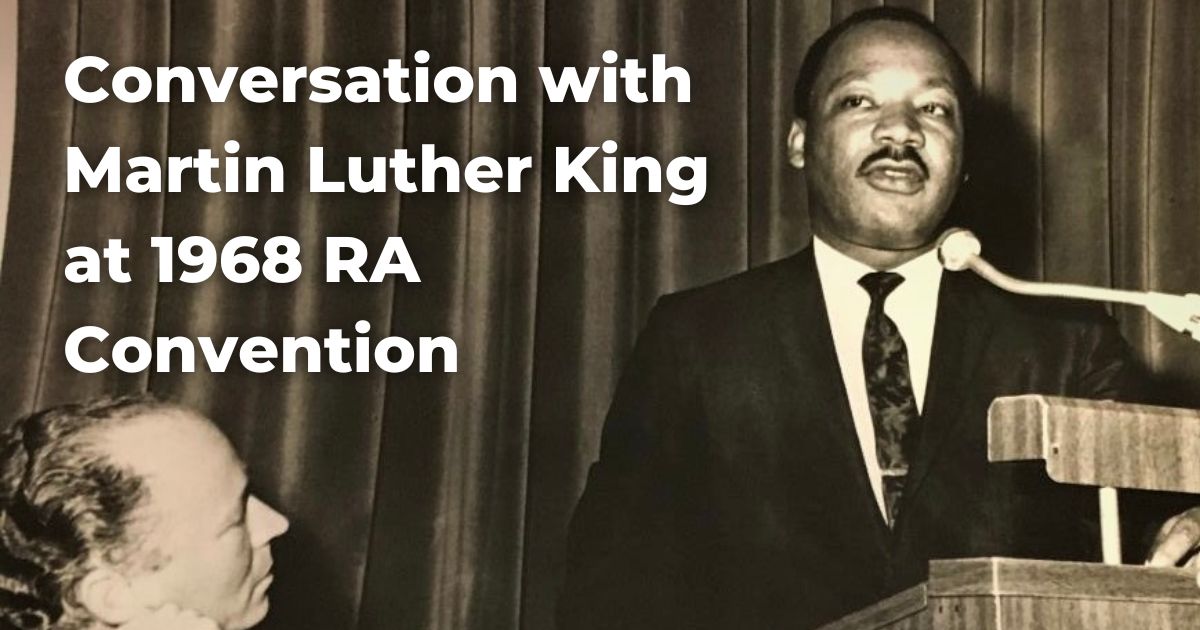

This is an interview between Rabbi Everett Gendler and Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 at the 68th Annual Rabbinical Assembly Convention.

The piece has been formatted for readability and headings added by the editor. We have also included a table of contents. The language and style may reflect the time it was written.

Table of Contents

The written record of the interview begins with the following notice:

On the evening of March 25, 1968, ten days before he was killed, Dr. Martin Luther King, zikhrono livrakhah (of blessed memory), appeared at the sixty-eighth annual convention of the Rabbinical Assembly. He responded to questions which had been submitted in advance to Rabbi Everett Gendler, who chaired the meeting.

Here is a transcript of what was said that evening, beginning with the words of Professor Abraham Joshua Heschel, who presented Dr. King to the assembled rabbis:

Rabbi Dr. Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Introduction

Dr. Heschel: Where does moral religious leadership in America come from today? The politicians are astute, the establishment is proud, and the market place is busy. Placid, happy, merry, the people pursue their work, enjoy their leisure, and life is fair. People buy, sell, celebrate and rejoice. They fail to realize that in the midst of our affluent cities there are districts of despair, areas of distress.

Where does God dwell in America today? Is He at home with those who are complacent, indifferent to other people’s agony, devoid of mercy? Is He not rather with the poor and the contrite in the slums?

Dark is the world for me, for all its cities and stars. If not for the few signs of God’s radiance who could stand such agony, such darkness?

Where in America today do we hear a voice like the voice of the prophets of Israel? Martin Luther King is a sign that God has not forsaken the United States of America. God has sent him to us. His presence is the hope of America. His mission is sacred, his leadership of supreme importance to every one of us.

The situation of the poor in America is our plight, our sickness. To be deaf to their cry is to condemn ourselves.

Martin Luther King is a voice, a vision and a way. I call upon every Jew to harken to his voice, to share his vision, to follow in his way. The whole future of America will depend upon the impact and influence of Dr. King.

May everyone present give of his strength to this great spiritual leader, Martin Luther King.

Dr. King’s Introductory Remarks

Dr. King: I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to be here this evening and to have the opportunity of sharing with you in this significant meeting, but I do want to express my deep personal appreciation to each of you for extending the invitation. It is always a very rich and rewarding experience when I can take a brief break from the day-to-day demands of our struggle for freedom and human dignity and discuss the issues involved in that struggle with concerned friends of good will all over our nation. And so I deem this a real and a great opportunity.

Another thing that I would like to mention is that I have heard “We Shall Overcome” probably more than I have heard any other song over the last few years. It is something of the theme song of our struggle, but tonight was the first time that I ever heard “We Shall Overcome” in Hebrew, so that, too, was a beautiful experience for me, to hear that great song in Hebrew.

It is also a wonderful experience to be here on the occasion of the sixtieth birthday of a man that I consider one of the truly great men of our day and age, Rabbi Heschel. He is indeed a truly great prophet.

I’ve looked over the last few years, being involved in the struggle for racial justice, and all too often I have seen religious leaders stand amid the social injustices that pervade our society, mouthing pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities. All too often the religious community has been a tail light instead of a head light.

But here and there we find those who refuse to remain silent behind the safe security of stained glass windows, and they are forever seeking to make the great ethical insights of our Judeo-Christian heritage relevant in this day and in this age. I feel that Rabbi Heschel is one of the persons who is relevant at all times, always standing with prophetic insights to guide us through these difficult days.

He has been with us in many of our struggles. I remember marching from Selma to Montgomery, how he stood at my side and with us as we faced that crisis situation. I remember very well when we were in Chicago for the Conference on Religion and Race. Eloquently and profoundly he spoke on the issues of race and religion, and to a great extent his speech inspired clergymen of all the religious faiths of our country; many went out and decided to do something that they had not done before. So I am happy to be with him, and I want to say Happy Birthday, and I hope I can be here to celebrate your one hundredth birthday.

I am not going to make a speech. We must get right to your questions. I simply want to say that we do confront a crisis in our nation, a crisis born of many problems. We see on every hand the restlessness of the comfortable and the discontent of the affluent, and somehow it seems that this mammoth ship of state is not moving toward new and more secure shores but toward old, destructive rocks.

It seems to me that all people of good will must now take a stand for that which is just, that which is righteous. Indeed, in the words of the prophet Amos, “Let justice roll down like the waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Our priorities are mixed up, our national purposes are confused, our policies are confused, and there must somehow be a reordering of priorities, policies and purposes. I hope, as we discuss these issues tonight, that together we will be able to find some guidelines and some sense of direction.

On Politics and Critics

Rabbi Everett Gendler: We begin now with some of the batches of questions. And since the question of confusion came up, and the problem of politics, perhaps we can begin with two or three questions which are rather immediate and relate to some very recent developments. One question is, “At this point, who is your candidate for President?” One question is, “If as it now seems Johnson and Nixon are nominated, do you have any suggestions as an alternative for those seeking a voice in the profound moral issues of the day?” And a third question in this general area of immediacy, “Would you please comment on Congressman Powell’s charge that you are a moderate, that you cater to Whitey, and also his criticism that you do not accept violence?” Some criticism!

Dr. King: Well, let me start with the first question. That is relatively easy for me because I have followed the policy of not endorsing candidates.

Somebody is saying stand, so I guess I’ll have to…

Rabbi Gendler: Might I say that since Dr. King anticipates a good bit of footwork next month, we thought perhaps this particular evening he could remain off his feet.

Dr. King: I’ll stand.

On the first question, I was about to say that I don’t endorse candidates. That has been a policy in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. We are a non-partisan organization. However, I do think the issues in this election are so crucial that it will be impossible for us to absolutely follow the past policy. I do think the voters of our nation need an alternative in the 1968 election, but I think we are in bad shape finding that alternative with simply Johnson on the one hand and Nixon on the other hand. I don’t see the alternative there. Consequently, I must look elsewhere. I think in the candidacy of both Senator Kennedy and Senator McCarthy we see an alternative. It is not definite, as you know, that President Johnson will be renominated. Of course, we haven’t had a situation since 1884 when an incumbent President was not renominated, if he wanted the nomination. But these are different days and it may well be that something will happen to make it possible for an alternative to develop within the Democratic party itself.

I think very highly of both Senator McCarthy and Senator Kennedy. I think they are both very competent men. I think they are relevant on the issues that are close to our hearts, and I think they are both dedicated men. So I would settle with either man being nominated by the Democratic party.

On the question of Congressman Powell and his recent accusation, I must say that I would not want to engage in a public or private debate with Mr. Powell on his views concerning Martin Luther King. Frankly, I hope I am so involved in trying to do a job that has to be done that I will not come to the point of dignifying some of the statements that the Congressman has made.

I would like to say, however, on the question of being a moderate, that I always have to understand what one means. I think moderation on the one hand can be a vice; I think on the other hand it can be a virtue. If by moderation we mean moving on through this tense period of transition with wise restraint, calm reasonableness, yet militant action, then moderation is a great virtue which all leaders should seek to achieve. But if moderation means slowing up in the move for justice and capitulating to the whims and caprices of the guardians of the deadening status quo, then moderation is a tragic vice which all men of good will must condemn.

I don’t see anything in the work that we are trying to do in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference which is suggestive of slowing up, which is suggestive of not taking a strong stand and a strong resistance to the evils of racial injustice. We have always stood up against injustices. We have done it militantly. Now, so often the word “militant” is misunderstood because most people think of militancy in military terms. But to be militant merely means to be demanding and to be persistent, and in this sense I think the non-violent movement has demonstrated great militancy. It is possible to be militantly non-violent.

On the question of appealing to “Whitey,” I don’t quite know what the Congressman means. But here again I think this is our problem which must be worked out by all people of good will, black and white. I feel that at every point we must make it very clear that this isn’t just a Negro problem, that white Americans have a responsibility, indeed a great responsibility, to work passionately and unrelentingly for the solution of the problem of racism, and if that means constantly reminding white society of its obligation, that must be done. If I have been accused of that, then I will have to continue to be accused.

Finally, I have not advocated violence. The Congressman is quite right. I haven’t advocated violence, because I do not see it as the answer to the problem. I do not see it as the answer from a moral point of view and I do not see it as the answer from a practical point of view. I am still convinced that violence as the problematic strategy in our struggle to achieve justice and freedom in the United States would be absolutely impractical and it would lead to a dead-end street. We would end up creating many more social problems than we solve, and unborn generations would be the recipients of a long and desolate night of bitterness. Therefore, I think non-violence, militantly conceived and executed, well-organized, is the most potent weapon available to the black man in his struggle for freedom and human dignity.

On the Extremist Elements of the Black Community’s Fight Against Segregation

Rabbi Gendler: Having raised several points that some of the questions referred to, we may proceed by a further exploration of some of these elements, Dr. King, and perhaps we could begin with several questions that relate to your evaluation of the internal mood of the black community.

Let me share some of the formulations of these questions with you. “How representative is the extremist element of the Negro community?” “How do we know who really represents the Negro community?” “If we are on a committee and there is a Negro militant and a Negro moderate, how shall a concerned white conduct himself?” “What is your view of the thinking in some Negro circles which prefers segregation and separatism, improving the Negro’s lot within this condition? How do you see Black Power in this respect?” “Black militants want complete separation. You speak of integration. How do you reconcile the two?” “How can you work with those Negroes who are in complete opposition to your view, and I believe correct view, of integration?”

Dr. King: Let me start off with the question, “How representative are the extremist elements in the black community?” I assume when we say extremist elements we mean those who advocate violence, who advocate separatism as a goal. The fact is that these persons represent a very small segment of the Negro community at the present time. I don’t know how the situation will be next year or the year after next, but at the present time the vast majority of Negroes in the United States feel that non-violence is the most effective method to deal with the problems that we face.

Polls have recently revealed this, as recently as two or three months ago. Fortune magazine conducted a pretty intensive poll, others have conducted such polls, and they reveal that about 92 percent of the Negroes of America feel that there must be some non-violent solution to the problem of racial injustice. The Fortune poll also revealed that the vast majority of the Negroes still feel that the ultimate solution to the problem will come through a meaningfully integrated society.

Now let me move into the question of integration and separation by dealing with the question of Black Power. I’ve said so often that I regret that the slogan Black Power came into being, because it has been so confusing. It gives the wrong connotation. It often connotes the quest for black domination rather than black equality. And it is just like telling a joke. If you tell a joke and nobody laughs at the joke and you have to spend the rest of the time trying to explain to people why they should laugh, it isn’t a good joke. And that is what I have always said about the slogan Black Power. You have to spend too much time explaining what you are talking about. But it is a slogan that we have to deal with now.

I debated with Stokely Carmichael all the way down the highways of Mississippi, and I said, “Well, let’s not use this slogan. Let’s get the power. A lot of ethnic groups have power, and I didn’t hear them marching around talking about Irish Power or Jewish Power; they just went out and got the power; let’s go out and get the power.” But somehow we managed to get just the slogan.

I think everybody ought to understand that there are positives in the concept of Black Power and the slogan, and there are negatives.

Let me briefly outline the positives. First, Black Power in the positive sense is a psychological call to manhood. This is desperately needed in the black community, because for all too many years black people have been ashamed of themselves. All too many black people have been ashamed of their heritage, and all too many have had a deep sense of inferiority, and something needed to take place to cause the black man not to be ashamed of himself, not to be ashamed of his color, not to be ashamed of his heritage.

It is understandable how this shame came into being. The nation made the black man’s color a stigma. Even linguistics and semantics conspire to give this impression. If you look in Roget’s Thesaurus you will find about 120 synonyms for black, and right down the line you will find words like smut, something dirty, worthless, and useless, and then you look further and you find about 130 synonyms for white and they all represent something high, noble, pure, chaste—right down the line. In our language structure, a white lie is a little better than a black lie. Somebody goes wrong in the family and we don’t call him a white sheep, we call him a black sheep. We don’t say whitemail, but blackmail. We don’t speak of white-balling somebody, but black-balling somebody.

The word black itself in our society connotes something that is degrading. It was absolutely necessary to come to a moment with a sense of dignity. It is very positive and very necessary. So if we see Black Power as a psychological call to manhood and black dignity, I think that’s a positive attitude that I want my children to have. I don’t want them to be ashamed of the fact that they are black and not white.

Secondly, Black Power is pooling black political resources in order to achieve our legitimate goals. I think that this is very positive, and it is absolutely necessary for the black people of America to achieve political power by pooling political resources. In Cleveland this summer we did engage in a Black Power move. There’s no doubt about that. I think most people of good will feel it was a positive move. The same is true of Gary, Indiana. The fact is that Mr. Hatcher could not have been elected in Gary if black people had not voted in a bloc and then joined with a coalition of liberal whites. In Cleveland, black people voted in a bloc for Carl Stokes, joining with a few liberal whites. This was a pooling of resources in order to achieve political power.

Thirdly, Black Power in its positive sense is a pooling of black economic resources in order to achieve legitimate power. And I think there is much that can be done in this area. We can pool our resources, we can cooperate, in order to bring to bear on those who treat us unjustly. We have a program known as Operation Breadbasket in SCLC, and it is certainly one of the best programs we have. It is a very effective program and it’s a simple program. It is just a program which demands a certain number of jobs from the private sector—that is, from businesses and industry. It demands a non-discriminatory policy in housing. If they don’t yield, we don’t argue with them, we don’t curse them, we don’t bum the store down. We simply go back to our people and we say that this particular company is not responding morally to the question of jobs, to the question of being just and humane toward the black people of the community, and we say that as a result of this we must withdraw our economic support.

That’s Black Power in a real sense. We have achieved some very significant gains and victories as a result of this program, because the black man collectively now has enough buying power to make the difference between profit and less in any major industry or concern of our country. Withdrawing economic support from those who will not be just and fair in their dealings is a very potent weapon.

Political power and economic power are needed, and I think these are the positives of Black Power.

I would see the negatives in two terms. First, in terms of black separatism. As I said, most Negroes do not believe in black separatism as the ultimate goal, but there are some who do and they talk in terms of totally separating themselves from white America. They talk in terms of separate states, and they really mean separatism as a goal. In this sense I must say that I see it as a negative because it is very unrealistic.

The fact is that we are tied together in an inescapable network of mutuality. Whether we like it or not and whether the racist understands it or not, our music, our cultural patterns, our poets, our material prosperity and even our food, are an amalgam of black and white, and there can be no separate black path to power and fulfillment that does not ultimately intersect white routes. There can be no separate white path to power and fulfillment, short of social disaster, that does not recognize the necessity of sharing that power with black aspirations for freedom and justice.

This leads me to say another thing, and that is that it isn’t enough to talk about integration without coming to see that integration is more than something to be dealt with in esthetic or romantic terms. I think in the past all too often we did it that way. We talked of integration in romantic and esthetic terms and it ended up as merely adding color to a still predominantly white power structure.

What is necessary now is to see integration in political terms where there is sharing of power. When we see integration in political terms, then we recognize that there are times when we must see segregation as a temporary way-station to a truly integrated society. There are many Negroes who feel this; they do not see segregation as the ultimate goal. They do not see separation as the ultimate goal. They see it as a temporary way-station to put them into a bargaining position to get to that ultimate goal, which is a truly integrated society where there is shared power.

I must honestly say that there are points at which I share this view. There are points at which I see the necessity for temporary segregation in order to get to the integrated society. I can point to some cases. I’ve seen this in the South, in schools being integrated and I’ve seen it with Teachers’ Associations being integrated. Often when they merge, the Negro is integrated without power. The two or three positions of power which he did have in the separate situation passed away altogether, so that he lost his bargaining position, he lost his power, and he lost his posture where he could be relatively militant and really grapple with the problems. We don’t want to be integrated out of power; we want to be integrated into power.

And this is why I think it is absolutely necessary to see integration in political terms, to see that there are some situations where separation may serve as a temporary way-station to the ultimate goal which we seek, which I think is the only answer in the final analysis to the problem of a truly integrated society.

I think this is the mood which we find in the black community, generally, and this means that we must work on two levels. In every city we have a dual society. This dualism runs in the economic market. In every city, we have two economies. In every city, we have two housing markets. In every city, we have two school systems. This duality has brought about a great deal of injustice, and I don’t need to go into all that because we are all familiar with it.

In every city, to deal with this unjust dualism, we must constantly work toward the goal of a truly integrated society while at the same time we enrich the ghetto. We must seek to enrich the ghetto immediately in the sense of improving the housing conditions, improving the schools in the ghetto, improving the economic conditions. At the same time, we must be working to open the housing market so there will be one housing market only. We must work on two levels. We should gradually move to disperse the ghetto, and immediately move to improve conditions within the ghetto, which in the final analysis will make it possible to disperse it at a greater rate a few years from now.

On The Relationship Between the Black and Jewish Community

Rabbi Gendler: Considering both the enlightenment and encouragement which I think many of us received just now from Dr. King’s portrayal of the prevalent mood in the black community, we might move on to another complex of questions relating, Dr. King, to the prevailing mood in the black community which also would benefit from some clarification by you. This is what we might call the area of black and Jewish communal relations.

“What steps have been undertaken and what success has been noted in convincing anti-Semitic and anti-Israel Negroes, such as Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, and McKissick, to desist from their anti-Israel activity?” “What effective measures will the collective Negro community take against the vicious anti-Semitism, against the militance and the rabble-rousing of the Browns, Carmichaels, and Powells?” “Have your contributions from Jews fallen off considerably? Do you feel the Jewish community is copping out on the civil rights struggle?” “What would you say if you were talking to a Negro intellectual, an editor of a national magazine, and were told, as I have been, that he supported the Arabs against Israel because color is all important in this world? In the editor’s opinion, the Arabs are colored Asians and the Israelis are white Europeans. Would you point out that more than half of the Israelis are Asian Jews with the same pigmentation as Arabs, or would you suggest that an American Negro should not form judgments on the basis of color? What seems to you an appropriate or an effective response?”

Dr. King: Thank you. I’m glad that question came up because I think it is one that must be answered honestly and forthrightly.

First let me say that there is absolutely no anti-Semitism in the black community in the historic sense of anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism historically has been based on two false, sick, evil assumptions. One was unfortunately perpetuated even by many Christians, all too many as a matter of fact, and that is the notion that the religion of Judaism is anathema. That was the first basis for anti-Semitism in the historic sense.

Second, a notion was perpetuated by a sick man like Hitler and others that the Jew is innately inferior. Now in these two senses, there is virtually no anti-Semitism in the black community. There is no philosophical anti-Semitism or anti-Semitism in the sense of the historic evils of anti-Semitism that have been with us all too long.

I think we also have to say that the anti-Semitism which we find in the black community is almost completely an urban Northern ghetto phenomenon, virtually non-existent in the South. I think this comes into being because the Negro in the ghetto confronts the Jew in two dissimilar roles. On the one hand, he confronts the Jew in the role of being his most consistent and trusted ally in the struggle for justice in the civil rights movement. Probably more than any other ethnic group, the Jewish community has been sympathetic and has stood as an ally to the Negro in his struggle for justice.

On the other hand, the Negro confronts the Jew in the ghetto as his landlord in many instances. He confronts the Jew as the owner of the store around the corner where he pays more for what he gets. In Atlanta, for instance, I live in the heart of the ghetto, and it is an actual fact that my wife in doing her shopping has to pay more for food than whites have to pay out in Buckhead and Lennox. We’ve tested it. We have to pay five cents and sometimes ten cents a pound more for almost anything that we get than they have to pay out in Buckhead and Lennox Square where the rich people of Atlanta live.

The fact is that the Jewish storekeeper or landlord is not operating on the basis of Jewish ethics; he is operating simply as a marginal businessman. Consequently the conflicts come into being. I remember when we were working in Chicago two years ago, we had numerous rent strikes on the West Side. And it was unfortunately true that the persons whom we had to conduct these strikes against were in most instances Jewish landlords. Now sociologically that came into being because there was a time when the West Side of Chicago was almost a Jewish community. It was a Jewish ghetto, so to speak, and when the Jewish community started moving out into other areas, they still owned the property there, and all of the problems of the landlord came into being.

We were living in a slum apartment owned by a Jew in Chicago along with a number of others, and we had to have a rent strike. We were paying $94 for four run-down, shabby rooms, and we would go out on our open housing marches in Gage Park and other places and we discovered that whites with five sanitary, nice, new rooms, apartments with five rooms out in those areas, were paying only $78 a month. We were paying twenty percent tax.

It so often happens that the Negro ends up paying a color tax, and this has happened in instances where Negroes have actually confronted Jews as the landlord or the storekeeper, or what-have-you. And I submit again that the tensions of the irrational statements that have been made are a result of these confrontations.

I think the only answer to this is for all people to condemn injustice wherever it exists. We found injustices in the black community. We find that some black people, when they get into business, if you don’t set them straight, can be rascals. And we condemn them. I think when we find examples of exploitation, it must be admitted. That must be done in the Jewish community too.

I think our responsibility in the black community is to make it very clear that we must never confuse some with all, and certainly in SCLC we have consistently condemned anti-Semitism. We have made it clear that we cannot be the victims of the notion that you deal with one evil in society by substituting another evil. We cannot substitute one tyranny for another, and for the black man to be struggling for justice and then turn around and be anti-Semitic is not only a very irrational course but it is a very immoral course, and wherever we have seen anti-Semitism we have condemned it with all of our might.

We have done it through our literature. We have done it through statements that I have personally signed, and I think that’s about all that we can do as an organization to vigorously condemn anti-Semitism wherever it exists.

On the Middle East crisis, we have had various responses. The response of some of the so-called young militants again does not represent the position of the vast majority of Negroes. There are some who are color-consumed and they see a kind of mystique in being colored, and anything non-colored is condemned. We do not follow that course in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and certainly most of the organizations in the civil rights movement do not follow that course.

I think it is necessary to say that what is basic and what is needed in the Middle East is peace. Peace for Israel is one tiling. Peace for the Arab side of that world is another thing. Peace for Israel means security, and we must stand with all of our might to protect its right to exist, its territorial integrity. I see Israel, and never mind saying it, as one of the great outposts of democracy in the world, and a marvelous example of what can be done, how desert land almost can be transformed into an oasis of brotherhood and democracy. Peace for Israel means security and that security must be a reality.

On the other hand, we must see what peace for the Arabs means in a real sense of security on another level. Peace for the Arabs means the kind of economic security that they so desperately need. These nations, as you know, are part of that third world of hunger, of disease, of illiteracy. I think that as long as these conditions exist there will be tensions, there will be the endless quest to find scapegoats. So there is a need for a Marshall Plan for the Middle East, where we lift those who are at the bottom of the economic ladder and bring them into the mainstream of economic security.

This is how we have tried to answer the question and deal with the problem in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and I think that represents the thinking of all of those in the Negro community, by and large, who have been thinking about this issue in the Middle East.

On Changes Needed in the System

Rabbi Gendler: Thank you very much, Dr. King. Perhaps we could share now a few questions relating to some of the domestic issues of poverty. A couple of them ask about the Kerner Report. “If the Kerner Report recommendations are implemented, will it make a difference?” “What is your opinion of the report of the Kerner Commission?”

Another raises the question of people of good intentions wanting to deal with slum problems and hardly knowing what to do, feeling that most of the simple tutoring and palliative efforts in the community may not amount to much, given the entire context of the system. It speaks of the power structure, the establishment finding funds for supersonic transports, moon projects, technological developments which are mere luxuries, for Vietnam, but not for those pressing needs which affect millions here at home. “Can you suggest why the establishment seems to work this way? Is it an accident or does it have deeper causes? What seem to you the minimal changes needed in the system in order to achieve some greater measure of social justice and equality?”

And perhaps related to this is the question of some of the realistic goals of the poor peoples’ campaign to be held in Washington beginning April 22nd.

Dr. King: Thank you. I want to start this answer by reiterating something that I said earlier, and that is that we do face a great crisis in our nation. Even though the President said today that we have never had it so good, we must honestly say that for many people in our country they’ve never had it so bad. Poverty is a glaring, notorious reality for some forty million Americans. I guess it wouldn’t be so bad for them if it were shared misery, but it is poverty amid plenty. It is poverty in the midst of an affluent society, and I think this is what makes for great frustration and great despair in the black community and the poor community of our nation generally.

In the past in the civil rights movement we have been dealing with segregation and all of its humiliation, we’ve been dealing with the political problem of the denial of the right to vote. I think it is absolutely necessary now to deal massively and militantly with the economic problem. If this isn’t dealt with, we will continue to move as the Kerner Commission said, toward two societies, one white and one black, separate and unequal. So the grave problem facing us is the problem of economic deprivation, with the syndrome of bad housing and poor education and improper health facilities all surrounding this basic problem.

This is why in SCLC we came up with the idea of going to Washington, the seat of government, to dramatize the gulf between promise and fulfillment, to call attention to the gap between the dream and the realities, to make the invisible visible. All too often in the rush of everyday life there is a tendency to forget the poor, to overlook the poor, to allow the poor to become invisible, and this is why we are calling our campaign a poor peoples’ campaign. We are going to Washington to engage in non-violent direct action in order to call attention to this great problem of poverty and to demand that the government do something, more than a token, something in a large manner to grapple with the economic problem.

We know, from my experiences in the past, that the nation does not move on questions involving genuine equality for the black man unless something is done to bring pressure to bear on Congress, and to appeal to the conscience and the self-interest of the nation.

I remember very well that we had written documents by the Civil Rights Commission at least three years before we went to Birmingham, recommending very strongly all of the things that we dramatized in our direct action in Birmingham. But the fact is that the government did not move, Congress did not move, until we developed a powerful, vibrant movement in Birmingham, Alabama.

Two years before we went into Selma, the Civil Rights Commission recommended that something be done in a very strong manner to eradicate the discrimination Negroes faced in the voting area in the South. And yet nothing was done about it until we went to Selma, mounted a movement and really engaged in action geared toward moving the nation away from the course that it was following.

I submit this evening that we have had numerous documents, numerous studies, numerous recommendations made on the economic question, and yet nothing has been done. The things that we are going to be demanding in Washington have been recommended by the President’s Commission on Technology, Automation and Economic Progress. These same things were recommended at our White House Conference on Civil Rights. The Urban Coalition came into being after the Detroit riot, and recommended these things.

The Kerner Commission came out just a few days ago recommending some of the same things that we will be demanding. I think it is basically a very sound, realistic report on the conditions, with some very sound recommendations, and yet nothing has been done. Indeed, the President himself has not made any move toward implementing any of the recommendations of that Commission. I am convinced that nothing will be done until enough people of good will get together to respond to the kind of movement that we will have in Washington, and bring these issues out in the open enough so that the Congressmen, who are in no mood at the present time to do anything about this problem, will be forced to do something about it.

I have seen them change in the past. I remember when we first went up and talked about a civil rights bill in 1963, right after it had been recommended by President Kennedy on the heels of the Birmingham movement. Mr. Dirksen was saying that it was unconstitutional, particularly Title I dealing with integrated public accommodations. He was showing us that it was unconstitutional. Yet we got enough people moving—we got rabbis moving, we got priests moving, we got Protestant clergymen moving, and they were going around Washington and they were staying on top of it, they were lobbying, they were saying to Mr. Dirksen and others that this must be done.

Finally, the Congress changed altogether. One day when Senator Russell saw that the civil rights bill would be passed and that the Southern wing could not defeat it, he said, “We could have blocked this thing if these preachers hadn’t stayed around Washington so much.”

Now the time has come for preachers and everybody else to get to Washington and get this very recalcitrant Congress to see that it must do something and that it must do it soon, because I submit that if something isn’t done, similar to what is recommended by the Kerner Commission, we are going to have organized social disruption, our cities are going to continue to go up in flames, more and more black people will get frustrated, and the extreme voices calling for violence will get a greater hearing in the black community.

So far they have not influenced many, but I contend that if something isn’t done very soon to deal with this basic economic problem to provide jobs and income for all America, then the extremist voices will be heard more and those who are preaching non-violence will often have their words falling on deaf ears. This is why we feel that this is such an important campaign.

We need a movement now to transmute the rage of the ghetto into a positive constructive force. And here again we feel that this movement is so necessary because the anger is there, the despair is growing every day, the bitterness is very deep, and the leader has the responsibility of trying to find an answer. I have been searching for that answer a long time, over the last eighteen months.

I can’t see the answer in riots. On the other hand, I can’t see the answer in tender supplications for justice. I see the answer in an alternative to both of these, and that is militant non-violence that is massive enough, that is attention-getting enough to dramatize the problems, that will be as attention-getting as a riot, that will not destroy life or property in the process. And this is what we hope to do in Washington through our movement.

We feel that there must be some structural changes now, there must be a radical re-ordering of priorities, there must be a de-escalation and a final stopping of the war in Vietnam and an escalation of the war against poverty and racism here at home. And I feel that this is only going to be done when enough people get together and express their determination through that togetherness and make it clear that we are not going to allow any military-industrial complex to control this country.

One of the great tragedies of the war in Vietnam is that it has strengthened the military-industrial complex, and it must be made clear now that there are some programs that we can cut back on—the space program and certainly the war in Vietnam—and get on with this program of a war on poverty. Right now we don’t even have a skirmish against poverty, and we really need an all out, mobilized war that will make it possible for all of God’s children to have the basic necessities of life.

What Specific Role Can Rabbis Play in the Civil Rights Struggle?

Rabbi Gendler: Because Dr. King must still meet tonight at least briefly with certain men from particular areas in the country, and because Reverend Young must also meet with some men from the Washington area immediately after this session, regretfully we have time for only one more question.

Although Dr. King is probably a bit weary and it is even conceivable that some of you are, I must say I very much regret that we haven’t more time to pick up some of the supplementary questions. Yet we have time really for only one last question, and I should imagine that, knowing the mood of the Rabbinical Assembly, the final questions have been asked in these kinds of terms, Dr. King.

One is, “What can we best do as rabbis to further the rights and equal status of our colored brethren?” Another is, “What specific role do you think we as rabbis can play in this current civil rights struggle? What role do you see for our congregants? How can all of us who are concerned participate with you in seeking this goal of social justice?”

Dr. King: Thank you very much for raising that because I do think that is a good note to end on, and I would hope that somehow we can get some real support, not only for the over-all struggle, but for the immediate campaign ahead in the city of Washington.

Let me say that we have failed to say something to America enough. I’m very happy that the Kerner Commission had the courage to say it. However difficult it is to hear, however shocking it is to hear, we’ve got to face the fact that America is a racist country. We have got to face the fact that racism still occupies the throne of our nation. I don’t think we will ultimately solve the problem of racial injustice until this is recognized, and until this is worked on.

Racism is the myth of an inferior race, of an inferior people, and I think religious institutions, more than any other institutions in society, must really deal with racism. Certainly we all have a responsibility—the federal government, the local governments, our educational institutions. But the religious community, being the chief moral guardian of the overall community should really take the primary responsibility in dealing with this problem of racism, which is largely attitudinal.

So I see one specific job in the educational realm: destroying the myths and the half-truths that have constantly been disseminated about Negroes all over the country and which lead to many of these racist attitudes, getting rid once and for all of the notion of white supremacy.

I think also I might say, concerning the Washington campaign, that there is a need to interpret what we are about or will be about in Washington because the press has gone out of its way in many instances to misinterpret what we will be doing in Washington.

There is a need to interpret to all of those who worship in our congregations what poor people face in this nation, and to interpret the critical nature of the problem. We are dealing with the problem of poverty. We must be sure that the people of our country will see this as a matter of justice.

The next thing that I would like to mention is something very practical and yet we have to mention it if we are going to have movements. We are going to bring in the beginning about 3,000 people to Washington from fifteen various communities. They are going to be poor people, mainly unemployed people, some who are too old to work, some who are too young to work, some who are too physically disabled to work, some who are able to work but who can’t get jobs. They are going to be coming to Washington to bring their problems, to bring their burdens to the seat of government, and to demand that the government do something about it.

Being poor, they certainly don’t have any money. I was in Marks, Mississippi the other day and I found myself weeping before I knew it. I met boys and girls by the hundreds who didn’t have any shoes to wear, who didn’t have any food to eat in terms of three square meals a day, and I met their parents, many of whom don’t even have jobs. But not only do they not have jobs, they are not even getting an income. Some of them aren’t on any kind of welfare, and I literally cried when I heard men and women saying that they were unable to get any food to feed their children.

We decided that we are going to try to bring this whole community to Washington, from Marks, Mississippi. They don’t have anything anyway. They don’t have anything to lose. And we decided that we are going to try to bring them right up to Washington where we are going to have our Freedom School. There we are going to have all of the things that we have outlined and that we don’t have time to go into now, but in order to bring them to Washington it is going to take money.

They’ll have to be fed after they get to Washington, and we would hope that those who are so inclined, those who have a compassion for the least of these God’s children, will aid us financially. Some will be walking and we’ll be using church buses to get them from point to point. Some will be coming up on mule train. We’re going to have a mule train coming from Mississippi, connecting with Alabama, Georgia, going right on up, and in order to carry that out you can see that financial aid will be greatly needed.

But not only that. We need bodies to bring about the pressure that I have mentioned to get Congress and the nation moving in the right direction. The stronger the number, the greater this movement will be.

We will need some people working in supportive roles, lobbying in Washington, talking with the Congressmen, talking with the various departments of government, and we will need some to march with us as we demonstrate in the city of Washington. Some have already done this, like Rabbi Gendler and others. When we first met him it was in Albany, Georgia and there along with other rabbis and Protestant clergymen and Catholic clergymen we developed a movement. And there have been others—as I said earlier, Rabbi Heschel in Selma and other movements.

The more of this kind of participation that we can get, the more helpful it will be, for after we get the 3,000 people in Washington, we want the non-poor to come in in a supportive role. Then on June fifteenth we want to have a massive march on Washington. You see, the 3,000 are going to stay in Washington at least sixty days, or however long we feel it is necessary, but we want to provide an opportunity once more for thousands, hundreds of thousands of people to come to Washington, reminiscent of March 1963 when thousands of people said we are here because we endorse the demands of the poor people who have been here all of these weeks trying to get Congress to move. We would hope that as many people in your congregations as you can find will come to Washington on June fifteenth.

You can see that it is a tremendous logistics problem and it means real organization, which we are getting into. We would hope that all of our friends will go out of their way to make that a big day, indeed the largest march that has ever taken place in the city of Washington.

These are some of the things that can be done. I’m sure I’ve missed some, but these are the ones that are on my mind right now and I believe that this kind of support would bring new hope to those who are now in very despairing conditions. I still believe that with this kind of coalition of conscience we will be able to get something moving again in America, something that is so desperately needed.

Rabbi Gendler: I think that all of us, Dr. King, recall the words of Professor Heschel at the beginning of this evening. He spoke of the word, the vision, and the way that you provide. We certainly have heard words of eloquence, words which at the same time were very much to the point, and through these I think we have the opportunity now to share more fully in your vision.

As for the way, it is eminently clear that the paths you tread are peaceful ones leading to greater peace. You may be sure that not only have we heard your words and not only do we share your vision, but many of us will take advantage of the privilege of accompanying you in further steps on the path that all of us must tread.

Thank you, Dr. King.

Above photo used courtesy of the Rabbinical Assembly.

Author

-

Exploring Judaism is the digital home for Conservative/Masorti Judaism, embracing the beauty and complexity of Judaism, and our personal search for meaning, learning, and connecting. Our goal is to create content based on three core framing: Meaning-Making (Why?), Practical Living (How?), and Explainers (What?).

View all posts