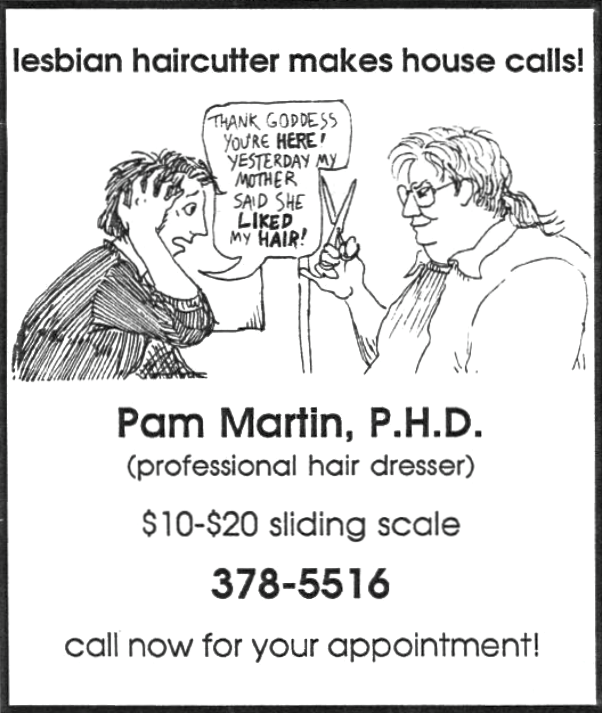

This Alison Bechdel comic may perplex some straight and cisgender readers. But, to members of the LGBTQ+ community, this comic references the trend of queer and lesbian women wearing their hair in gender nonconforming, unconventional ways.

In reality, they do not typically choose these hairstyles for the purpose of alienating mothers. LGBTQ+ identifying people often wear clothing, accessories, makeup, hairstyles, and pins to make their queer identities known to others. These aesthetic markers can be subtle, recognizable only to those “in the know,” or can be loud, explicit declarations of their identity. This method of using visual cues to express one’s queer identity to others is called “queer flagging.”

This concept is not new to the Jewish community. R’ Ovadia Yosef (Z”L), the former Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel, wrote,

“Nowadays, wearing a kippah is more than just a pious custom… The kippah on one’s head serves as a clear symbol to distinguish between one who serves Hashem and one who does not, for Torah-observant Jews take care to always walk around with their heads covered and the kippah has become a religious symbol which causes one to be imbued with fear of Heaven.”

Making oneself visible as a religious Jew is, in situations where one can do so safely, imperative to communicate one’s commitment to religious observance.

Clothing, religious attire, and hair indicate one’s community. For the purposes of this article, I will call this “Jewish flagging.” Jewish flagging allows one to visually identify oneself as Hasidic or Yeshivish, Iraqi or Yemenite, Haredi, Da’ati, Masorti, or secular.

Pictured: Yemenite Jews, including Rabbi Yahya Yusuf Musa; the Hasidic Satmar Rebbe; members of the Israeli rock band, “Shlepping Nachas”

Pictured: Modern Orthodox fashion bloggers Chaya Chanin and Simi Polonsky; Haredi women in Beit Shemesh, Israel; Reform rabbinical students at Hebrew Union College

Transgender Jews, however, do not merely wear religious garb to represent their religious affiliation. Their religious garb can be used to reflect their gender identity and queerness. It can also be used to make visible an affiliation to a community that does not standardize its clothing.

In 2021-2023, I interviewed 45 transgender Jews from across the United States. Many of the participants shared that they wore some form of religious garb outside of a synagogue on a regular basis.

Some chose to wear a mitpachat/tichel (headscarf), despite attending Reform or Conservative synagogues where doing so was unusual. Intriguingly, most identified as single and nonbinary. In Orthodox communities, the headscarf performs the function of communicating a woman’s marital status. Yet, for these transgender individuals, the headscarf does not always communicate gender and marital status within the Jewish community. Instead, it reflects an allegiance to Jewish womanhood and makes Jewishness visible in the broader public sphere.

Other participants chose to leave the corners of their hair uncut, in the style of peyot, and/or wear tzitzit (fringes worn on garments with four corners, typically on a garment called a tallit katan). Rose said,

“I recently started wearing tzitzit… I want to walk out on the street and for people to know that I’m Jewish. I used to be able to do that by wearing a kippah, but now that makes me feel dysphoric and wrong. People might see me and be upset that a woman is wearing tzitzit… but at least they know that I’m Jewish.”

In addition to being less explicitly masculine, peyot and tzitzit perform a special function that kippot and Stars of David cannot. They signal Jewishness to other Jews while completely “flying under the radar” among most non-Jews (or, in my experience, being read as a queer fashion choice).

Pictured: mesh tallit katan with tzitzit; a black mesh shirt with a rainbow stripe; queer musician Orville Peck wearing his typical fringed mask and a fringed jacket

Pictured: queer-identifying TikTok user @gosageurself with “deathhawk” hairstyle; Haredi boys with peyot

Many participants, including transgender men, nonbinary people, and some transgender women, shared that they wear kippot/yarmulkes every day. The styles of kippot varied, with participants favoring a range of materials, colors, and patterns. Some opted to crochet their own kippot in the colors of a relevant pride flag. This allows them to signal their Jewish and queer identities simultaneously. For many, the kippah functioned as an affirmation of masculinity, or to flag gender-nonconforming identities among nonbinary and female participants.

Queer flagging can be a double-edged sword. Being visibly queer can make you a target for homophobic or transphobic harassment. In the same way, being visibly Jewish often leads to as many negative interactions as positive ones. As Vik put it,

“Sometimes you can switch out of whatever gender presentation you prefer and into a safer, ‘passing’ version… and sometimes you can’t. That’s true for both being trans and being Jewish.”

Personally, I have had multiple strangers threaten me with violence after seeing my kippah. Female strangers have also hugged or touched me without my consent. This would be inappropriate in any situation but holds extra weight for religious Jewish men. In another example, Dex shared that he has frequently been nonconsensually touched and kissed by “anti-religion” non-Jews or those whom Dex identified as “fetishizing” religiously-modest women.

For many Jews and queer people, it is possible to “pass” as members of the majority. It is often beneficial to do so, whether for physical safety or to avoid discrimination. For Jews, the choice to wear a kippah or a baseball cap comes with the added weight of potential danger. Being identifiably Jewish can make them a target of antisemitic attacks. For trans people, wearing makeup or an alternative hairstyle can lead to harassment from both strangers and loved ones. However, despite the many risks, transgender Jews are still making the choice to be visible, and to engage with traditional Jewish observance, including observances that are gendered.

As you engage with the queer Jews in your community, I invite you to lean into curiosity. Ask non-judgmental, open-ended questions about their experiences. Try to connect with both your commonalities and differences. And reflect: what led you to make the choices you made about your clothes, hairstyle, or Jewish garb?

Notes:

“What Is The Hanky Code? The History Behind Gay Flagging and How to Do It Today.”

“Wearing A Kippa On One’s Head,” Halacha Yomit.

Author

-

Matt Lacoff is a Jewish educator and transgender man. He currently oversees a pre-b’nei mitzvah program in New York. The following article reflects the findings of his 2021-2023 academic research, in which he interviewed 45 transgender Jews about their experiences. You can read his other article here.

View all posts